From Living Woods Issue 59

WHERE HAVE ALL THE FLOWERS GONE?

Ecologists and woodland owners ROY AND KATHRYN NELSON longed for a woodland with a rich and vibrant understorey. When their young wood in Northern Ireland failed to produce one, they applied academic rigour to the problem and have used their findings to offer practical advice.

In 2001 we decided to convert 10 acres of our farm to a small wood. The area chosen for this was a meadow that had been in permanent grass for the past 30 years. We had an idea that we were returning the land to its once former state, as the area is locally known in Gaelic as ‘Killymuck’ which translates as the wooded area of the pig, but there were now no pigs and very few trees. The future we imagined was a wood with a mix of broadleaved trees (mainly ash, oak, birch, and maple) which would have a beautiful woodland floor covered by a mass of herbaceous flowers. They would provide a fragrance in spring and a vision of wonder. This was something we remembered from our youths. Sixteen years later the trees had grown well, but the utopian vision had yet to be realised and it made us think ‘Where have all the flowers gone?’

In 2017 Kathryn was pursuing research at Queen’s University Belfast when the opportunity arose to investigate this question. This lack of ground flora appeared to be a common problem for other woodlands. Consequently, a study was launched to examine 30 newly planted broadleaf woodlands that had been established around the year 2000. Kathryn visited these woods once in spring and then again in early summer, and the findings provide practical advice which could be adopted to actively encourage colonisation of new woods by herbaceous ground flora.

The small woodlands visited had mostly been established on the least productive areas of farmland, like our own. Although none of the sites had an arable history prior to planting, the recommendations from this investigation are applicable to many contrasting situations.

Woodland ground flora behaviour

The quintessential woodland that many dream of has a variety of trees and a vibrant herbaceous ground flora. For many, this could be a blanket of bluebells, but in reality can be a combination of many other species. Woodland flora are generally classified with respect to their inherent ability to reproduce, and those inhabiting woodlands are conventionally recognised as either Ancient Woodland Indicator Species (wood specialists) or Woodland Indicator Species (shade tolerant). This classification is used in many situations as an aid to identify the age and history of woodlands. The research, however, revealed a more precise classification system based upon the abilities of the herbaceous plants to migrate into the woods This helps to explain why there were different patterns observed. These new classifications are:

Ancient edge huggers – typically, ransom, wood sorrel, hart’s tongue fern, dog violet, and wood anemone. These plants colonise the edges and expand slowly into the wood.

Expansionists – typically, primrose, greater stitchwort, golden saxifrage, bluebell, and enchanter’s nightshade. These plants have greater potential to colonise and, compared to the edge huggers, disperse relatively fast into the heart of the wood.

Woodland dispersers – typically, jack-in-the-pulpit, male fern, and herb bennet. These plants have a more random dispersal within the wood but have the potential to expand quickly to new sites.

Exploiter – lesser celandine. This plant takes advantage of opportunities related to light or moisture availability and, compared to the other groups, can rapidly blanket the ground in local situations.

Management and habitat factors

Several important influential management and habitat factors were found to affect the successful colonisation of herbaceous ground flora. A more active management programme of the woodland prior to and during early establishment aids the colonisation dynamic. The following points should be considered:

1. Many woods are ‘isolated’ and it is important to ensure connectivity to sources of existing woodland plants. This can be achieved via the habitat corridors that exist within the countryside, namely hedges, which are often the last refuges of these woodland species. Mature hedges must be ‘maintained’ prior to tree planting, as coarse weeds can impact on the success of herbaceous seed and propagule dispersal.

2. Woodlands planted close to riparian zones (riverbanks) have a high potential for increasing colonisation. However, these areas must be monitored, as streams and rivers can be sources of aggressive invasive species.

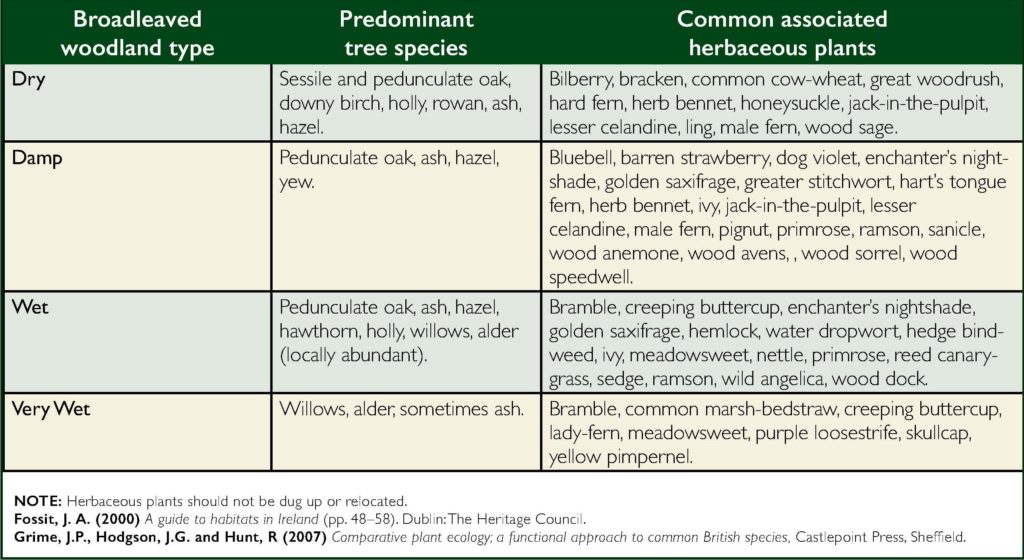

3. In newly planted woodland the tree species chosen does not affect the initial colonisation; this related more to the density and mix of the trees. Active early thinning encourages the migration of many of the herbaceous species desired. When mature, however, the planted tree species will influence final herbaceous ground floor composition.

4. Owners and managers can bring in plants from elsewhere, but this may cause a ‘founder’ effect – the loss of genetic variation that can occur when new plants are introduced that are of a different genetic makeup from the endemic species. Plants of local provenance do contribute more fully to the woodland biome. The well-intentioned but ill-judged planting of ‘alien’ species such as Spanish bluebells in the desire to achieve a traditional woodland with a blue carpet of flowers in the spring must be prevented. However, waiting for natural self-seeding can be problematic as there may only be a few woodland plants growing nearby or some species may even be locally extinct. Therefore, before any planting occurs, the edges of the site should be surveyed, and management practices adopted that increase and enhance the plants of local provenance to colonise the new wood.

In conclusion, to achieve a woodland that has an associated diverse herbaceous flora requires certain management practices and landscape features. These include

• a mosaic of interconnected woodlands and connected corridors of existing hedges rich in plant species

• the monitoring of riparian zones to reduce the likelihood of invasive species establishing

• a management programme during the early stages of the young wood.

Taken together, these will help to increase species dispersal and create the woodlands of our hopes and dreams.

Reference: Kathryn Nelson, Roy Nelson and William Ian Montgomery (2021) ‘Colonisation of farmland deciduous plantations by woodland

ground flora’, Arboricultural Journal

KATHRYN NELSON is an artist and a PhD research student at Queen’s University Belfast.

DR ROY NELSON is an Honorary Senior Lecturer at Queen’s University Belfast. He uses quantitative analysis and social science research methods to help investigate ecological and related problems.