Britain went to bed on the night of 15th October 1987 having heard weather forecaster Michael Fish reassure the nation that it might be a bit windy, but there was certainly no prospect of a hurricane engulfing the country.

Britain went to bed on the night of 15th October 1987 having heard weather forecaster Michael Fish reassure the nation that it might be a bit windy, but there was certainly no prospect of a hurricane engulfing the country.

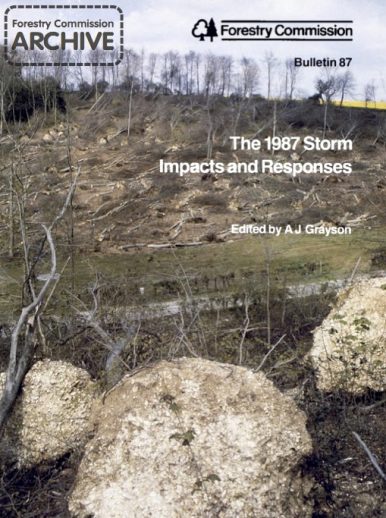

The state of the southern Britain the next morning suggested that Mr Fish may have been a little conservative in his estimation. Gales of more than 100 mph had roared across the country, ripping off roofs, toppling power lines and uprooting millions of trees. It was a night to remember and in many woodlands the impact is still clear 30 years later.

I certainly don’t wish to experience it again

Arborist Christopher Sparkes was working for Hampshire County Council in 1987 and he recalls his experience of the storm. ‘Well where do I start? As the wind started to blow hard on the 15th, I was called out by Hampshire County Council to clear trees on Three Maids Hill. We started cutting away at trees 80 feet tall which had fallen down either side of us. We had to pull out as it became too dangerous.

‘My father-in-law and I stood on either side of a large beech in a woodland. It was swaying backwards and forwards and we stood on either side, using it as a see-saw, going up in air about six feet. It was down the next day. I’ve never seen anything as bad since and I certainly don’t wish to experience it again.’

In south-east England, where the greatest damage occurred, gusts of 70 knots or more were recorded continually for three or four consecutive hours. The damage is well documented: 18 people died, many buildings were damaged and it is estimated that around 15 million trees were uprooted. Sevenoaks lost six of its eponymous trees. Many of the fallen trees were mature and the immediate change to the landscape was shocking. In retrospect, however, many ecologists and arborists regard the storm almost as a beneficial event.

In south-east England, where the greatest damage occurred, gusts of 70 knots or more were recorded continually for three or four consecutive hours. The damage is well documented: 18 people died, many buildings were damaged and it is estimated that around 15 million trees were uprooted. Sevenoaks lost six of its eponymous trees. Many of the fallen trees were mature and the immediate change to the landscape was shocking. In retrospect, however, many ecologists and arborists regard the storm almost as a beneficial event.

Conifers planted earlier in the century as fast-growing timber crops were toppled, exposing large areas of woodland to the light which allowed new planting and self-seeded broadleaves to flourish in the ensuing years. The quality of the understorey in many woodlands also benefited, with a resultant improvement in biodiversity of species.

Meanwhile, Christopher was heavily involved in clearing the Hampshire roads. ‘We went up Romsey Road in Winchester to clear a tree which was blocking the main road. Once we started cutting, sparks flew and underneath the foliage we discovered a car which had been flattened by the tree. Fortunately, the driver got out safely. We spent the next two weeks clearing trees from main roads down to tiny roads. ‘In those days chainsaw certificates were not required: if you could use one, it was fine and the trees were cleared reasonably fast. How it would work now with all the paperwork and licenses involved, I don’t know. I think the UK would have ground to a halt waiting on paperwork.

Shaken beech

‘A lot of the beech that came down was near the end of life and the ferocity of the storm shook them so hard that the trees had the shakes. When shaken wood went through band saws at the mills it was like an explosion, snapping bandsaw blades. A lot of mills would not take it then, and all it was good for was firewood or was left to rot. ‘This is why woodland management is so crucial. Mature old trees need to be taken down, rather than waiting for them to fall down due to age, or to blow down as in the 1987 storm.’

In 1987 the destruction of so many valuable trees seemed catastrophic, but woodland owners and managers learnt many lessons. The Forestry Commission established the Windblow Task Force to provide advice to owners and to act as a focal point for information dissemination to the media, woodland owners and wood processing organisations. In 1989 the Forestry Commission published The 1987 Storm: Impacts and Responses, which was a comprehensive examination of the storm and its effect on Britain’s woodlands. (It is available to download via the Forestry Commission’s publication archive here.) One important revelation was that plantation woodlands were less resilient: trees planted closely together grew tall with shallow root systems and were therefore vulnerable in high winds. The traditional system of coppice with standards allowed trees to become resilient over time – and provided a good example of survival of the fittest.

In 1987 the destruction of so many valuable trees seemed catastrophic, but woodland owners and managers learnt many lessons. The Forestry Commission established the Windblow Task Force to provide advice to owners and to act as a focal point for information dissemination to the media, woodland owners and wood processing organisations. In 1989 the Forestry Commission published The 1987 Storm: Impacts and Responses, which was a comprehensive examination of the storm and its effect on Britain’s woodlands. (It is available to download via the Forestry Commission’s publication archive here.) One important revelation was that plantation woodlands were less resilient: trees planted closely together grew tall with shallow root systems and were therefore vulnerable in high winds. The traditional system of coppice with standards allowed trees to become resilient over time – and provided a good example of survival of the fittest.

By the mid-1990s ecologists realised that the storm had broken up monocultures in some woodlands and allowed natural regeneration of pioneer species such as birch. By 2007 many areas had regenerated naturally and required far less maintenance than areas that had been replanted with nursery stock, ‘One of the legacies we have learned from the Great Storm is that woodlands look after themselves pretty well,’ said forester Ray Hawes.

Thanks to Christopher Sparkes for sharing his memories.