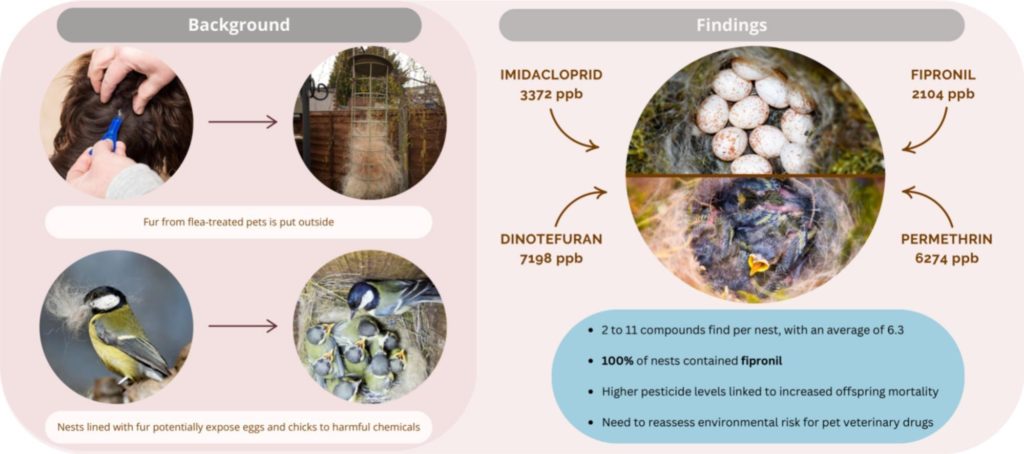

Recent research has highlighted the risk of environmental contamination from veterinary drugs regularly applied to dogs and cats to prevent fleas and ticks. A study published today that tested 103 birds’ nests found that they all contained insecticides used in spot-on treatments, shampoos, sprays and collars. The nests belonged to blue and great tits, which line their nests with fur. Nests with higher levels of insecticides were more likely to have unhatched eggs or dead chicks.

A study published in 2021 showed that the same insecticides, fipronil and imidacloprid, were present in virtually all of the water samples taken from twenty English rivers, with sites immediately downstream of wastewater works having the highest levels. This was followed by a 2024 study that quantified the routes by which this ‘down the drain’ contamination occurred, with owner handwashing, dog bathing and bed washing found to be significant sources. Given that most of the nation’s 22 million dogs and cats are routinely treated for fleas and ticks, this is likely to cause significant environmental pollution, with largely unknown consequences for wildlife.

Fipronil and imidacloprid are potent neurotoxins, designed to kill insects by disrupting the function of their nervous system. These chemicals do not specifically target pest species – they have the potential to impact all insects and also other animals, both directly due to physiological similarities and via knock-on ecological effects. Negative effects on pollinators such as bees have been particularly well-documented. As a result, fipronil was banned from agricultural use in the EU in 2017. Imidacloprid is a neonicotinoid, a type of insecticide that the EU banned for outdoor use but which continued to be granted ’emergency use’ in the UK until very recently. It is therefore somewhat anomalous that both of these highly toxic chemicals continue to be available for routine home application to pets.

Many woodland owners also own dogs, or have dogs being walked in their woodlands, and responsible owners normally want to protect their dogs against the increased risk of being bitten by ticks in woods. However, most woodland owners are also keen to protect wildlife, to not contaminate ponds and streams, or expose nesting birds and their chicks to toxic dog fur. One recommended course of action is to minimise the use of tick and flea treatments, applying only when they are really needed. Martin Whitehead, vet and co-author of two of the studies, would like the profession to adopt a more responsible approach, for example by not allowing pet health plans to include monthly, year-round applications.

Some well-intentioned dog owners deliberately brush and leave dog hair in outdoor places such as woodlands for nesting birds to use. In light of recent findings this is obviously not advisable, nor is allowing treated dogs into ponds, however much they may enjoy this. Asking your woodland visitors with dogs to act likewise, informing them of the risks, would be a sensible approach to minimising contamination and helping to protect the resident wildlife. The Forestry Commission have some general guidance on managing dogs in woodlands which may also be useful.

For the health of the wider environment, a comprehensive re-evaluation of our approach to treating pets for fleas and ticks is likely to be required.