From Living Woods issue 60

Woodland manager JOHN CAMERON finds himself both bemused and bedazzled by this absorbing study of fungi and their impact on our environment.

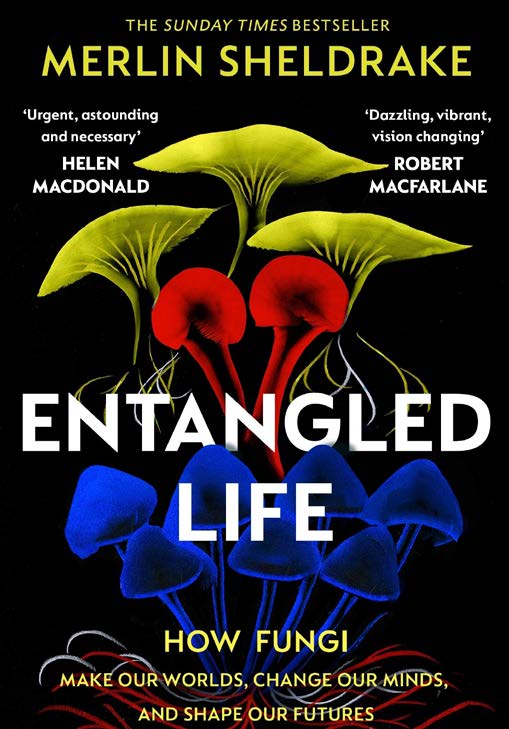

ENTANGLED LIFE

How fungi make our worlds, change our minds and shape our futures

Merlin Sheldrake

Vintage Books

Hardback £15.30

Paperback £9

ISBN: 978-1784708276

It seems extraordinary that fungi account for the largest interconnected organisms on the planet and yet, disappointingly, over 90% of species remain undocumented. Entangled Life introduces the reader to the incredible and almost unbelievable world of fungi on the micro and macro scale, with fascinating examples that illustrate just how adaptable they are. From the very smallest and most ancient origins on the planet, the reader is taken on a mind-expanding journey, detailing the intricate, interconnected relationship of fungi with the living world, and to some of the idiosyncratic and puzzling chemicals contained within them.

Entangled Life manages to be both at once a scholarly and scientific discourse which discusses the interconnectivity and dependency of the world around us, while at the same time entertaining readers with snippets of fact and folklore from around the globe. From the mystery and secrecy surrounding the hunt for the aromatic truffle, to the hallucinogenic and psychedelic effects of the chemicals contained in some mushrooms, the story weaves gently and methodically like the tentacles of mycelium growth that it is describing.

For the reader with scientific interest, numerous recounted laboratory experiments will doubtless interest, with insight into the function and purpose of fungi. Often the extraordinary results are unexpected and pose more questions than are answered. Examples include eating rubbish, surviving radioactivity and zombie ant-creation – just some of the many worldly examples of the tremendously intriguing behaviour of fungi.

While some of the more developed practices of fungi are explored, so too is the ancient relationship of fungi with algae, perhaps equal and symbiotic; or in a dark and sinister turn, perhaps not? Who benefits who, in this familiar interconnection of nature? Similarly, the unseen dependency of tree and plant root systems, almost entirely reliant on mycorrhizal associations, going back over 400 million years to its earliest recorded fossil records, but probably far longer. The ‘wood wide web’ is an easy-to-comprehend term that seems to encapsulate our feelings as woods people about the importance of diversity. And the implications of fungal associations with particular species of trees explains the prominence of birch and mountain ash, to name but a few, as particularly successful pioneer species of upland, marginal or nutrient-poor conditions.

A striking thought is that fungi are the destroyers of the world through decay and decomposition, but at the same time they are the constructors or composers. We are invited to consider how the planet would look, if all of the successes of life on our beautiful planet were not recycled by fungi: an astonishing mess comes to mind! Perhaps fungi are the housekeepers of the planet? Even the distinctly less-than-natural products made by man, such as plastics, petrochemicals, glyphosate weed killers and nerve agents come in for discussion, with some species or other of fungi developing a penchant for consuming these damaging creations.

The reader is left with hope and the distinct impression that it will be fungi that hold the key to saving the planet.